-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Economics

p-ISSN: 2166-4951 e-ISSN: 2166-496X

2013; 3(C): 74-81

doi:10.5923/c.economics.201301.13

Investigation of the Langer's Mindfulness Scale from an Industry Perspective and an Examination of the Relationship between the Variables

Chan Tze Leong, Amran Rasli

Faculty of Management, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, 81310, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Chan Tze Leong, Faculty of Management, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, 81310, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This paper reviews Langer's Mindfulness Scale from perspective of industry and factor structure. Confirmatory factor analysis was unable to replicate the findings of the previous multiple factor models that was based on university students and individuals in personal settings. Explanatory factor analysis revealed a two factor model. Results were compared to other empirical results. The relationship between the variables of mindfulness/mindlessness was examined to reveal strong correlation. This findings support an earlier empirical investigation of a two-factor mindfulness scale. Nonetheless, findings from a single case study do not construe similar findings from industry nature. Future validation studies could expand to other industries particularly having different mix of process and service orientation, respondents employed in support functions and respondents of large size and having different diversity. Mindfulness has positive association with individuals' education and division of employment. This result is consistent with studies in adaptive management.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Mindlessness, Factor Analysis, Industry, Empirical, Ellen Langer

Cite this paper: Chan Tze Leong, Amran Rasli, Investigation of the Langer's Mindfulness Scale from an Industry Perspective and an Examination of the Relationship between the Variables, American Journal of Economics, Vol. 3 No. C, 2013, pp. 74-81. doi: 10.5923/c.economics.201301.13.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Mindfulness has been examined by researchers in different perspectives namely as traits, cognition, emotion, meditation, constructs, stress-reduction and neuroscience [9],[33]. The level of trait mindfulness varies from each individual as it depends on levels of propensity and dispositional trait[6]. Mindfulness was used to assess differences in individuals from which personality scales were developed[15]. For mindfulness as a special state of consciousness, an individual uses sensory input and imply to pay attention in a unique manner and purposefully, into the present moment without pre-conceived judgement[23] to notice the surroundings for new things without falling into a tenacity of comparison, evaluation or renunciation unlike other cognitive processors[7]. An increasing number of studies focusing on mindfulness application particularly in the fields of psychology and neuroscience have impacted psychological well-being and its neurobiological correlates [20]. Several studies have supported links between mindfulness and positive psychology and that mindfulness could influence engagement in activities, judgement and decision making[27],[30]. Mindfulness from a pure western perspective is represented by Ellen Langer. She argued that the ability of individuals and organisations to achieve reliable performance in a changing environment depends on how individuals think, gather information, perceive the environment around them, and whether they could change their perspective to reflect the situation at hand. This cognitive state of mindfulness is distinct from the Buddhist traditional mindfulness meditation[34]. Studies show that the engagement of the attributes of mindlessness (the opposite of mindfulness) such as engaging in fewer cognitive processes, acting on "automatic pilot" mode, precluding attention to new information, relying on past categories and fixating on a single perspective without awareness that things could be otherwise, are demonstrated more frequently by individuals and organisations alike unconsciously[40]. By applying active differentiation and clarification of existing categories, a sophisticated cataloguing system with the ability to widen awareness, engagement and openness of new perspectives could be created. Through this approach, individuals could gain greater control of their mind by moving from semi automatic mode of awareness[41] to a "conscious" state that continually taps their mind's potential. Although the benefits from mindfulness application could be seen in practice, only few studies have examined mindfulness from an empirical perspective. This study answers the call for research by exploring the underlying factors of mindfulness[29].

2. Materials and Methods

- Most studies on Langer's Mindfulness scale (LMS) were carried out in a western setting[28],[35],[16] and few studies focus on a non-western industrial setting. The contribution of this study towards to the mindfulness literature could be seen from two methods. Firstly, it proposes to valid LMS in a non-western industry-type organisation by providing evidence for a robust and replicable factor structure. Secondly, it proposes to explore the relationship among the variables of mindfulness.

2.1. Measures and Statistical Analysis

- Individual's propensity for mindfulness/mindlessness was assessed with a 21-item self-reported survey emphasising on 4 factors namely novelty seeking, novelty producing, flexibility and engagement[28]. A person seeking novelty tends to demonstrate a propensity for an open and curious orientation to their surroundings. A person producing novelty shows a tendency to develop new content instead of relying on previous associations. Flexibility refers to the ability of the individuals to view content from different perspectives and to utilise the response from the circumstances or surroundings to effect the changes to their behaviour. An individual having high propensity for engagement is more likely to notice details of their relationship with the environment. The LMS scales were originally developed and published in English. Some of the items were revised to increase objectivity particularly by reducing double meaning, misunderstanding and by mitigating some cultural issues. They were subsequently translated to Bahasa Malaysia and were circulated in a bi-lingual survey form. The respondents indicate on a 5-point Likert scale (1=Never, 5=Always), their propensity of mindfulness. Thirteen items were normally scored and eight items were reversed score. The higher the score, the higher the propensity of mindfulness in the individual. The LMS maintained good reliability (Cronbach's α=0.776) although the factors reported lower reliability (Cronbach's α for novelty seeking, novelty producing, flexibility and engagement was 0.412, 0.248. 0.56 and 0.583 respectively). Prior to the statistical analysis, the variables were examined for their skewness, kurtosis and missing data. For 95% significance, the significance value for all items were determined at 0.000 for both Kolmogrov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk statistics. The skewness value between -1.078 to 0.700 and kurtosis value between -1.244 to 1.636 supported the normality distribution of all variables[14]. To address the missing data in the sample (representing 10.7% of the data points), missing values were replaced with values derived from the mean for that variable in order to meet the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) assumptions. Examination of histograms and q-q plots revealed no violations of homoscedasticity or normality. The sample consists of 300 employees in an integrated automotive organisation based in Malaysia involved from designing and research and development, to manufacturing and sale of its cars (including after sales services). The mean score of the entire LMS was 3.5763 (SD=0.48100) and the means of the items varied between 2.5540 (SD=0.85218) and 4.1745 (SD=0.75165).

2.2. Factor Analysis

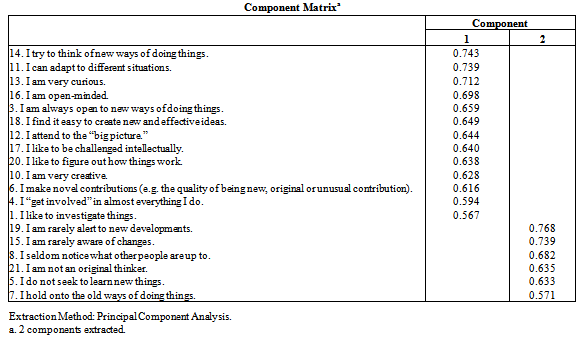

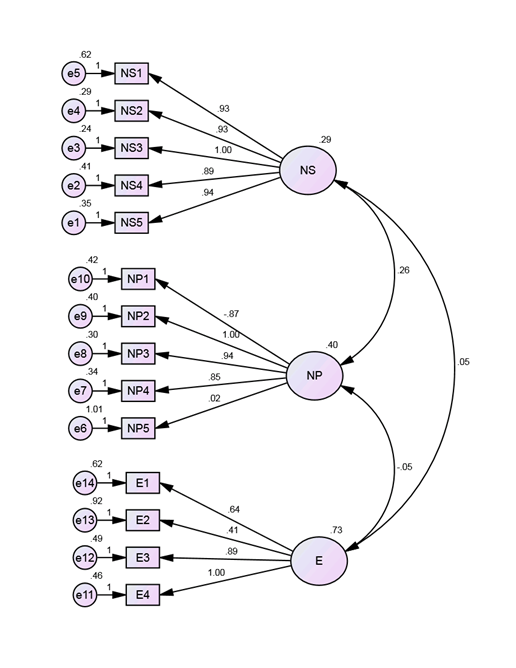

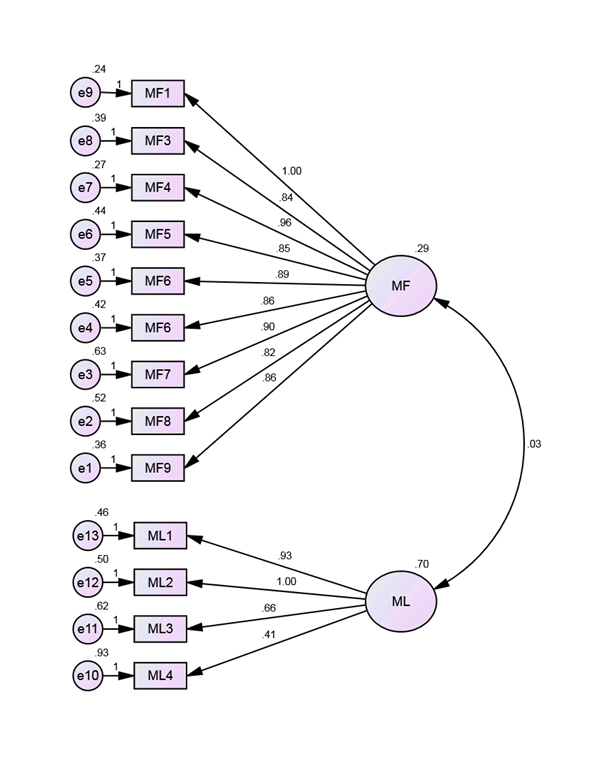

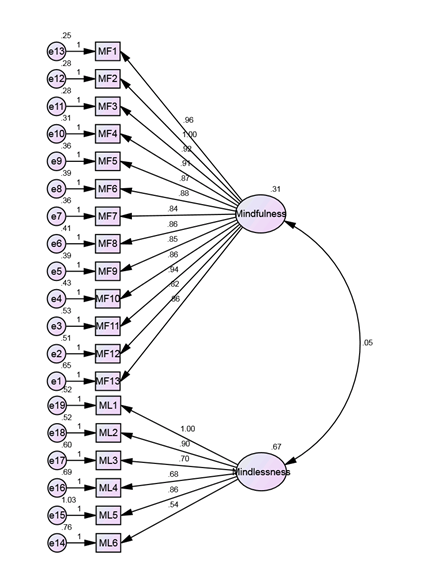

- A CFA was carried out against the three models, as presented in Figures 1 to 3. χ2 is a popular summary statistics tool to evaluate the accuracy of a structural equation model. However, if the sample is large, there could be a tendency to overestimate the fit[4]. Goodness of fit was primary assessed by χ2 value, CFI, RMSEA and SRMR. This was supplemented by other fit values to counteract the weakness of χ2. A good fit model should demonstrate a non-significant χ2, CFI≥0.90, RMSEA≤0.06 and SRMR≤0.08[21],[2]. Based on the four-factor model proposed by Langer and Bodner[28], the factor loadings and covariances are shown in Figure 1. The resulting fit indices of that model indicated a poor fit (i.e. χ2 (183) =919.23, p=0.000; CMIN/df=5.02; CFI=0.668; SRMR=0.1565; RMSEA=0.12; 90% on CI on RMSEA=0.11 to 0.12). However, an attempt to improve the results by modifying the indices was not successful. Based on the three-factor model proposed by Pirson et al.[35], the factor loadings and covariances are shown in Figure 2. The resulting fit indices of the original three- factor model indicated a poor fit (i.e., χ2 (74) =288.01, p=0.000; CMIN/df=3.89; CFI=0.83; SRMR=0.099; RMSEA=0.10; 90% on CI on RMSEA=0.01 to 0.11). However, an attempt to improve the results by modifying the indices was not successful. Analysis was further carried out on the two-factor model proposed by Haigh et al.[16] and the factor loadings and covariances are shown in Figure 3. Based on the suggested fit indices, the original three-factor model demonstrated a poor fit to the data, χ2 (103) =296.02, p=0.000; CMIN/df=2.87; CFI=0.87; SRMR=0.0767; RMSEA=0.08; 90% on CI on RMSEA=0.07 to 0.09. However, an attempt to improve the results by modifying the indices was not successful.

| Figure 1. Four-factor LMS |

| Figure 2. Three-factor LMS |

| Figure 3. Two-factor LMS |

|

| Figure 4. Two-factor revised LMS |

2.3. Correlation Analysis

- In their efforts to understand the determinants of mindfulness, researchers have focussed their attention on the key components as highlighted by Kabat-Zinn[23]. The propensity of mindfulness exercised could also depend on the background of the individuals. In this paper, we examine empirically to what extent selected mindfulness and mindlessness motives are related to mindfulness performance. The study finds positive association between mindfulness with individuals’ education and individuals employed in divisions that engage in multi-functional activities (including planning). Respondents having post graduate degree were demonstrating higher mindfulness(M=4.5488, SD=0.12620) than respondents having less than STPM/A-levels/diploma/ certificate (M=3.8067, SD=0.55298) and bachelor degree/ professional qualification (M=3.8301, SD=0.50237) with a small size effect. Respondents from Product Planning & Development division were demonstrating higher mindfulness (M=4.6000, SD=0.37448) than respondents from Manufacturing division (M=3.7985, SD=0.52724) and Automotive Parts (M=3.6465, SD=0.48557) with a medium size effect. The desire for mindfulness is counteracted by the increase in mindlessness activities in certain circumstances. Respondents aged 36-40 years old were demonstrating higher mindlessness (M=3.85, SD=0.548) than respondents aged more than 46 years old (M=3.75, SD=0.602) although the effect was a small size. The study also supports the impact of education and job grade towards mindlessness. Respondents having bachelor degree/professional qualification were demonstrating higher mindlessness (M=3.6000, SD=0.57300) than respondents having less than STPM/A-levels/diploma/certificate (M=3.2037,SD=0.76982) with a small size effect. Respondents who were executives were demonstrating higher mindlessness (M=3.5490, SD=0.61947) than respondents having less than STPM/ A-levels/ diploma/certificate (M=3.2391,SD=0.76665) with a small size effect. This result draws insight from the study by Gartner[13] suggesting mindlessness could be associated either with automaticity, routine, habit, stability, and continuity. The results support the view that higher levels of routine, automaticity or lack of distinctive learning could exist among the executives compared to the non-executives. Alternatively, it may be possible that the non-executives' engagement in innovative practices in the organization related to kaizen, innovative and creative circles and quality circles could mitigate the level of mindfulness. On the other hand, mindfulness nor mindlessness did not experience statistically significant when considering years of experience. Despite having long service employers, the lack of learning system that could configure and amass dynamic human resource capabilities to support the dynamic capabilities of the organisation could be a contributing factor towards cultivating mindlessness behaviour among individuals [19],[18]. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was utilised to examine the relationship between the variables. Evidence support a strong correlation between "I am rarely alert to new developments" with "I am rarely aware of changes" (r=0.582, n=300, p<0.0005). This result is consistent with other studies suggesting that attention is required to perceive change. In the absence of localized motion signals, attention is generally guided on the basis of high-level interest[36]. Studies show that during the times when the individuals' perception of a visual scene is often incomplete is when the individuals' selective nature of attention is allowed to pass by unnoticed as if they are irrelevant to the viewing task[32] and when they do not capture attention[31]. Only when the participants are instructed to look for it, the change is detected. While it is assumed that changes to a fixated object will be noticed unless spatial attention is focused on another part of the scene, other studies have suggested that change blindness may also exist at fixation[38]. So far, only one study has shown that mindfulness training may improve attention related behavioural responsiveness by changing the functioning of specific subcomponents of attention[22]. There was also evidence supporting a strong correlation between "I am open-minded" with "I can adapt to different situations" (r=0.546, n=300, p<0.0005), "I am always open to new ways of doing things" (r=0.532, n=300, p<0.0005), "I try to think of new ways of doing things" (r=0.510, n=300, p<0.0005) and "I am very curious" (r=0.500, n=300, p<0.0005). This correlation has some similarities with another two different correlations i.e. (i) between "I am very curious" with "I attend to the big picture" (r=0.507, n=300, p<0.0005) and "I can adapt to different situations" (r=0.525,n=300, p<0.0005); and between "I try to think of new ways of doing things" with "I am very curious" (r=0.595, n=300, p<0.0005) and "I can adapt to different situations" (r=0.517, n=300, p<0.0005). These strong correlations are consistent with studies in adaptive management. Studies suggest practising learning and reflecting in different ways of thinking such as regular exposure to different contexts and problems, being more exposed and reflecting on issues from different perspectives and continuously questioning and reflecting on those perspectives, could develop individuals to learn flexibility in different situations and deal more adaptively with complex systems[12]. In some ways, curious people are better adapt to organisational changes[17]. Perhaps, the common theme in this correlation could be linked to continuous learning and adaption to a changing or a complex environment. The strong correlation between "I am very curious" with "I make novel contributions" (r=0.532, n=300, p<0.0005) supports the conceptualisation of curiosity by Kasdan and Silvia[26] as the recognition, pursuit, and intense desire to explore novel, challenging and uncertain events. The results support the idea that both novelty and curiosity are determinants of exploration behaviour within individuals[3]. However, there is little evidence to support the perception that some things are only interesting to nearly everyone. This imperfection of curiosity suggests that there are differences in the extent of what people consider different things to be interesting[37]. Likewise, individuals may consider new things to be sometimes confusing and unpleasant and it may affect the outcome of the novelty seeking or outcome unless the individual exercises motivation in pursuit of the said novelty. Lastly, the strong correlation between "I find it easy to create new and effective ideas" with "I like to be challenged intellectually" (r=0.527, n=300, p<0.0005) was not surprising. This result suggest that the employees' desires to strive for innovative output at their workplace[10].

3. Conclusions

- Present findings indicate that the revised LMS is an internally consistent and a stable assessment tool. These results are of a particularly important to empirical research since they replicate the qualities of LMS independent of medical influences. These findings support the use of the revised 2-factor LMS as a valid and reliable instrument for assessing mindfulness among Malaysian employees.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Preparation of this article was supported by a grant from the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML